CER MODERN

ARTS CENTER

DESIGN

- Semra Uygur

- Özcan Uygur

PROJECT TEAM

- Necati Seren

- Güliz Erkan

- Ayhan Abanozcu

- İrem Erdinç

- Selen Poyraz

- Işıl Düzgün

- Ünsal Susam

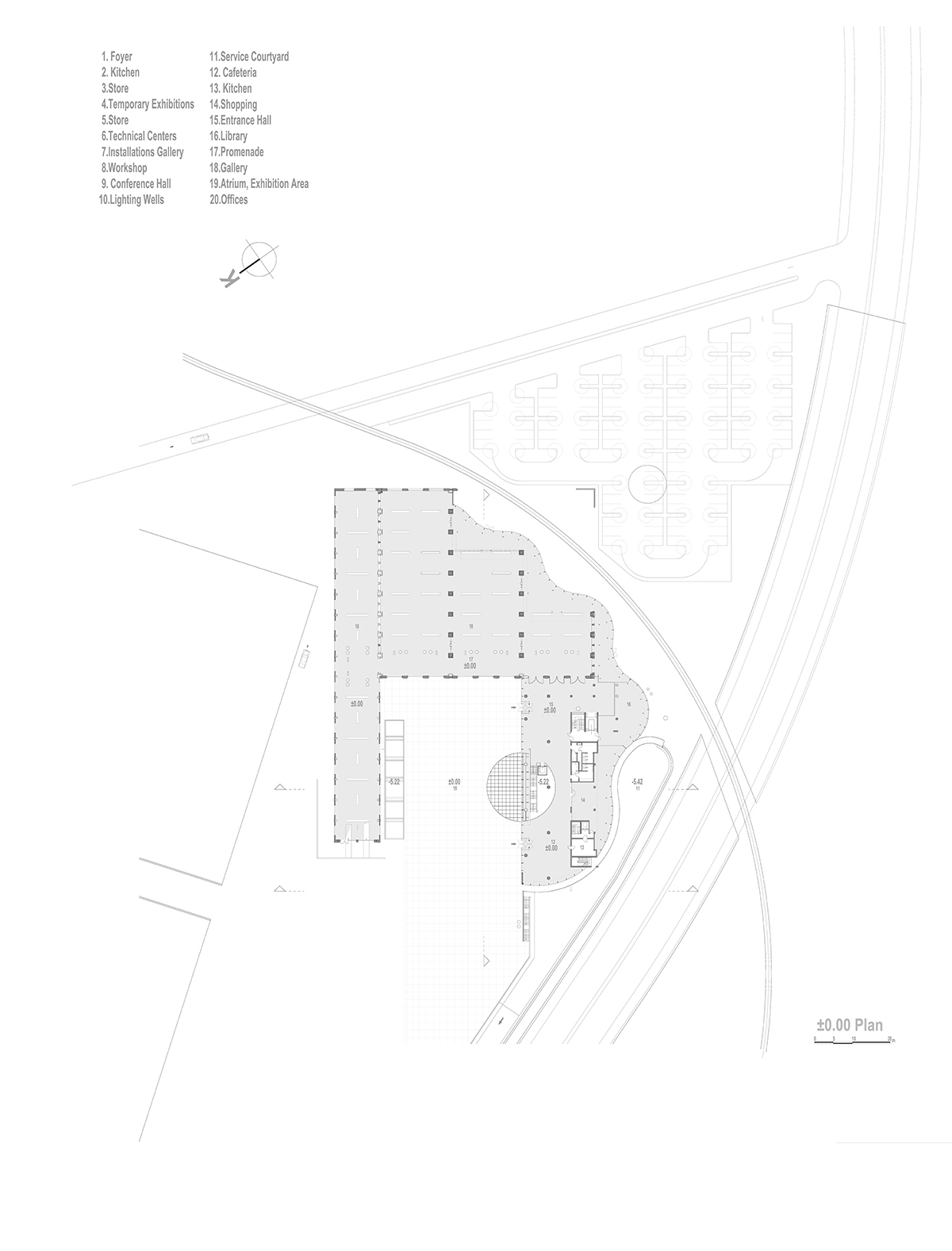

The history of the project goes back to 1990s, when a national competition was opened in 1992 for the design of presidential symphony orchestra concert hall on a vacant land between Ulus and Sıhhiye, the old and new quarters of Ankara. The site contained a segment of the railway, with old traction ateliers and train maintenance sheds (three identical units dating from 1920s, with a longer unit added later). Being four adjacent units in total, all were intended to be removed from the site. In 1995, after the architects of the winning project started work for the presidential symphony concert hall, decision was taken for the transformation of these old sheds into an art museum. In the meantime, the railroad was rerouted and two of the three identical units were partly demolished. The remaining sheds were in ruins, needing structural consolidation and mechanical installation to function as gallery spaces.

The contractor chosen for the restoration of the ateliers decided to work with the architects of

the

concert hall. The initial brief called for a “Contemporary Art Museum” (later named “Modern Arts

Center”) with gallery spaces and related facilities. The size and spatial features of the

ateliers were

compatible with the intended galleries; additional spaces were needed however, to serve as

multi-purpose

halls, museum store and cafe, small galleries and services. To meet the need, a modern building

was

annexed to the remaining portions of the sheds.

The guiding idea behind the project was to keep the relation of the site with the train. While

the

active train route is made visible from the interiors by means of a transparent wall wrapping

the old

and new buildings, the railroad tracks entering into the sheds are maintained on the timber

decking of

the courtyard. The new building is characterized on its outer edge with a continuous curvilinear

glass

wall, which the architects liken to a ‘roll bandage’ that wraps the injured historic building as

well

(specifically, the two half-demolished sheds).This enabled the new building to get firmly

connected to

the old, while the old could ‘stand up’ so to speak, with the aid of the new. Thus in the image

of a

walking stick, the annex undertook the strengthening of both the old sheds and the courtyard.

Forming

one wing of the U-shaped whole, the new building defines an outdoor space protected from the

vehicular

traffic. Entries to the building are from this courtyard. At the courtyard level, entrance hall

and

museum shop and cafe take place, besides main exhibition halls converted from the sheds. The

basement

floor accommodates additional galleries, auditorium, ateliers and services.

The Center is occupying a corner of the larger site reserved for the concert hall, which is still under construction. Thus the context is currently a non-place, surrounded by the construction site and parking lots (of the Center and the Court House nearby). The presence of the building has already raised the profile of the district, demonstrating the power of architecture in creating an urban magnet.

The building is fulfilling the need for a modern art center with its dynamic, uninterrupted spaces that accommodate changes for every new display and art event. Since its inauguration in 2010 April, the building has become a lively cultural hub for Ankara, hosting simultaneous exhibitions, conferences, performances, festivals and the like. Its courtyard is equally popular, used throughout all seasons for art installations, besides being an extension of the cafe. In summer nights it serves also as an outdoor cinema, frequented much by citizens of all age. After the completion of the concert hall, the center is expected to be part of larger urban ensemble.

Being much more than a renovation task, the project brought new life to a group of buildings that were seen as an expendable stock of ordinary service buildings alongside of the railway. In all its urban insignificance, the site embodied the memory of old times in the city. Remaining from the 1920s when the railways were nationalized, these train maintenance sheds witnessed the fervor of the Early Republican Era, and hence considered worth preserving for their intangible value.

From the architectural standpoint, the buildings conveyed the beginnings of modern vocabulary in ‘functional’ buildings as such. During the post-war period when building sector was deprived of skilled professionals and craftsmen, the sheds were constructed by unqualified labourers (excepting the ironwork by a German company). Being a rare example of industrial archaeology that has escaped demolition in Ankara, and due to its new function as a modern arts center, this adaptive reuse has presented an exemplary urban reclamation. The impact of the new structure contributed much to the historic building, resulting in a richer environment, having added new layers and meaning to the place. The project is significant in its integration of old and new; the modern additions display an architecture of 'courtesy' by surrounding the injured buildings with gentle boundaries. As for the modern building, an architecture suited to its place and time is aimed. Contextual compatibility and contemporariness in design have been given equal emphasis, creating sensitive building contours (in relation to the old building, the railway and traffic artery, and the sunken garden), while promoting a restrained modern vocabulary on the whole.

- Location

- Project

- Construction

- Structural Eng. Project

- Mechanical Eng. Project

- Electrical Eng. Project

- Consultants

- Client

- Construction Area

- Photos

- Altındağ, Ankara, Turkey

- 2000 - 2002

- 2000 - 2010

- Danyal Kubin, Prota Engineering

- Bahri Türkmen, Bahri Türkmen Engineering

- Mehmet S. Yurdakul

- Ali Artun (Art), Fuat Gökçe (Restoration)

- The Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Culture and Tourism

- 9.380m2

- Cemal Emden